A platform shoulder arthroplasty system has the potential advantage of allowing conversion to a reverse total shoulder arthroplasty without removing a well-fixed, well-positioned humeral stem.

These authors sought to use a review of the literature to evaluate the complications associated with humeral stem exchange versus retention in patients undergoing conversion shoulder arthroplasty with a platform shoulder arthroplasty system. They included 7 studies (236 shoulders), including 1 level III and 6 level IV studies. Pooled analysis demonstrated significantly higher overall complications (odds ratio, 6.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.48-19.13; P = .0002), fractures (odds ratio, 4.62; 95% CI, 1.14-18.67; P = .03), operative time (mean difference, 62.09 minutes; 95% CI, 51.17-73.01 minutes; P < .00001), and blood loss (mean difference, 260.06 mL; 95% CI, 165.30-354.83 mL; P < .00001) with humeral stem exchange. Stem exchange was also associated with increased risk of reoperation (P = .0437).

They point out the limitations of such a study: (1) none of the included studies were randomized and all but one were retrospective. These retrospective studies were at high risk of potential bias and (2) some convertible stems could not be retained because of incompatibility with length or appropriate positioning for reverse total shoulder.

They point out the limitations of such a study: (1) none of the included studies were randomized and all but one were retrospective. These retrospective studies were at high risk of potential bias and (2) some convertible stems could not be retained because of incompatibility with length or appropriate positioning for reverse total shoulder.

Comment: Many of the complications with stem removal arise because the stem was cemented or because an ingrowth prosthesis was used making safe removal difficult. Even if a platform stem was used, it may need to be removed because of loosening as shown in the figure below

or malpositing (the figure below shows a 'too high' stem placement), making conversion to a reverse with the existing stem impossible

or because the surgeon does not wish to use the reverse design associated with the original stem.

Here's a recent case that demonstrates the attractive feature of an impaction graft fixation: it allows safe removal removal of an anatomic stem from one company

and insertion of the reverse stem from another company at the desired hight and rotation.

Furthermore, as is now well-known, when an arthroplasty fails it can be difficult to know whether an infection is present. Stem removal is usually recommended if infection is suspected - removal that is much more difficult if the stem is cemented or has an ingrowth surface.

Finally, now surgeons are becoming more sophisticated in their ability to decide whether a primary reverse is likely to be necessary - so that many of the hemiarthroplasties previously performed for fracture and anatomic arthroplasties previously performed in the presence of cuff weakness would now receive a primary reverse.

Here's a prior post on the topic:

Conversion to Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty with and without Humeral Stem Retention:The Role of a Convertible-Platform Stem

These authors retrospectively reviewed 102 shoulders having revision of an anatomic shoulder arthroplasty to a reverse total shoulder. 73 of the shoulders had exchange of the humeral stem and 29 had retention of a convertible-platform humeral component stem.

Patients with retention had significantly shorter operative time, less blood loss and fewer intraoperative complications.

The authors conclude that shoulder arthroplasty systems utilizing a convertible-platform humeral stem offer an advantage when conversion to a reverse total shoulder is performed, provided that the stem is well-fixed and in proper position.

Comment: In that removal of a humeral stem - especially if it is bone ingrowth, cemented, or well fixed - can be difficult and risky, it is not surprising that those cases having stem removal had more complex surgeries and more complications.

the reasons for stem exchange are not. Specifically, it is not clear why over 70% of these cases had exchange of the stem. Possible reasons could include a loose stem, an improperly positioned stem (wrong height, wrong version), a stem that was not convertible, a stem that was not compatible with the reverse glenoid that the surgeon desired to use, a shoulder that was sufficiently tight that the stem required lowering to accommodate the glenosphere, the need to remove the humeral stem for glenoid exposure and infection. Thus, the use of a convertible stem does not assure that the stem should be retained in conversion to a reverse.

The need for convertible stems would be diminished if the indications for conversion were anticipated and managed. For example, older patients, patients with fragile or deficient rotator cuffs, patients with tuberosity malunions or non unions, and shoulders prone to instability may be better managed with a primary reverse arthroplasty as opposed to 'trying' an anatomic.

In our practice we do not find systems with ‘platform’ stems attractive because many failures of anatomic arthroplasties are related to improper placement of the stem as shown below.

It seems doubtful that a platform design would facilitate revision of the cases shown below to a reverse.

Here's a reprise of some of the prior blog posts on this topic.

An anatomic arthroplasty can fail for many reasons, including malposition, instability, delayed cuff failure and pseudo paralysis. In these situations consideration can be given to conversion of the anatomic prosthesis to a reverse total shoulder as shown here. As demonstrated in that post out preferred method for managing a failed anatomic arthroplasty is to completely remove the existing implant, obtain cultures, and then implant the reverse prosthesis. This approach allows full access to the glenoid and optimal positioning of the humeral component of the reverse. Removal of the anatomic implant is almost always possible and is particularly straightforward if it was inserted using impaction grafting.

In certain cases, such as that shown here, a well fixed stem can be retained and the proximal end converted to a reverse total shoulder with insertion of a glenosphere. Here's another post regarding conversion with retention of the anatomic stem.

Recently, there has been the advent of 'platform' prostheses, in which a humeral stem is fixed in the humeral canal that can be attached to either an anatomic or a reverse proximal humeral prosthesis. For examples, see here, here, here, and here.

It is important to recognize that in a reverse, (1) the glenosphere is placed inferiorly on the glenoid face, (2) the proximal humeral part of the reverse is bigger than that of an anatomic humeral arthroplasty and (3) the soft tissue tensioning considerations of a reverse are different from those of an anatomic arthroplasty. Therefore, the proximal-distal positioning of the humeral component needs to be fine tuned to achieve the ideal reverse arthroplasty. While some systems provide various adaptors to adjust the height, inclination and version of the proximal humeral prosthesis, the flexibility in positioning is limited by the use of the 'platform' fixed in the humeral canal.

Fortunately, we now have a clearer understanding of the indications for a reverse total shoulder, so that the needs for convertible prostheses is diminishing. For example, it is becoming evident that proximal humeral fractures in elderly individuals are often best managed by a primary reverse total shoulder - the idea of 'trying' an anatomic arthroplasty that is convertible to a reverse later is not so appealing. Similarly, individuals with arthritis, cuff deficiency, and instability are also best managed by a primary reverse.

See related post here.

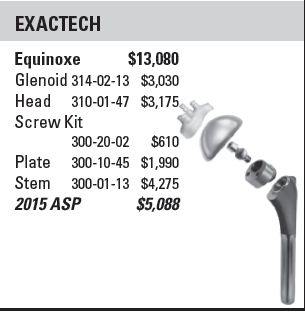

One of the aspects lacking in articles about platform and other types of new shoulder prostheses is the incremental cost of the implant. This information is necessary to determine the value (benefit/cost) of the device. The question becomes, for 100 anatomic arthroplasties, how many successful conversions to reverses would be necessary to justify the incremental cost of (1) the implant and (2) the learning curve?

In our practice, revision of an anatomic to a reverse prosthesis is required almost exclusively in cases where the index procedure is done elsewhere. Often there are problems with stem fixation or positioning that require stem removal, even if 'in theory' the platform stem is convertible to a reverse.

One of the advantages of fixation of a humeral stem with impaction grafting is that - should conversion to a reverse prosthesis be required - the stem can be easily removed and the reverse stem inserted at the desired height and version.

Finally, infection with Propionibacterium is now recognized as a not unusual complication of shoulder arthroplasty. A well fixed stem for a platform prosthesis makes prosthesis exchange complicated.

Future studies will be helpful in determining the cost effectiveness of convertibles in shoulder arthroplasty.

===

The reader may also be interested in these posts:

Information about shoulder exercises can be found at this link.

Use the "Search" box to the right to find other topics of interest to you.

You may be interested in some of our most visited web pages including: shoulder exercises, shoulder arthritis, total shoulder, ream and run, reverse total shoulder, CTA arthroplasty, and rotator cuff surgery as well as the 'ream and run essentials' See from which cities our patients come.