"In many conditions requiring shoulder arthroplasty, the capsule and ligaments are contracted and therefore excessively limit the range of rotation. Shoulder arthroplasty tends to further tighten the capsule because the degenerated humeral head is replaced by a larger one, and because a glenoid component is added to the surface of the glenoid bone, consuming more space than the degenerated cartilage it replaces.

Thus, the components "stuff" the joint. Unless sufficient capsular releases have been performed to accommodate this stuffing, the joint is "overstuffed" so that the motion is restricted."

This phenomenon is demonstrated in a laboratory model where progressively thicker humeral head and glenoid implants were used.

|

It is of interest that overstuffing not only limits the range of motion but also increases the stiffness of the shoulder (i.e., the torque necessary to achieve a specified position). The overstuffed joint requires additional muscle force to achieve desired motion, as shown below.

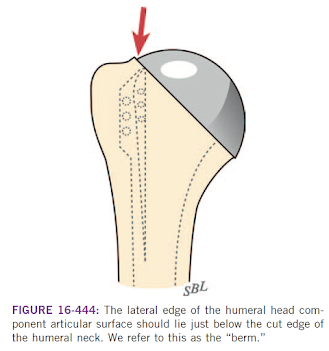

Because shoulder arthroplasties are commonly performed on joints with preoperative muscle stiffness, capsular contracture, osteophytes that can block the range of motion, loss of articular cartilage, and - not infrequently - humeral and glenoid bone deformity and wear, it is difficult to determine the optimal thickness of components until after soft tissue releases and osteophyte resection have been performed.

The final component selection needs to be made intraoperatively with the trial components in place and applying the "40, 50, 60 rules"; the combination of soft tissue management and implant selection should allow

(1) 40 degrees of external rotation with the the subscapularis held at the re-insertion point on the lesser tuberosity,

(2) 50% translation when the humeral head is pressed posteriorly, and

(3) 60 degrees of internal rotation when the arm is abducted to 90 degrees as shown below.

Common causes of overstuffing include

(1) components that are too thick (note that metal backing of a glenoid component can contribute to overstuffing).

producing a cam effect when the arm is abducted ("B" below).

Careful intraoperative attention to these technical details enables the surgeon to optimize mobility and stability of the arthroplasty.

Many thanks to Steve Lippitt for his great art work!

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frederick.matsen

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

How you can support research in shoulder surgery Click on this link.

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interest