Long term followup carries the risk of progressively losing patients that have poor results so that the results appear to get better with time.

These authors make a case for a more rigorous reporting of outcome data to account for the proportion of patients who do not reach the thresholds for clinically important improvement. They point out that reporting p values for the average improvement in patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can overestimate the benefit of treatment.

Instead the clinical significance of the outcome should be reported using clinical thresholds

such as

-the minimum clinically important difference (MCID), a threshold indicating the smallest change in the treatment outcome that a patient perceives as beneficial, and

-the patient acceptable symptom state (PASS), a threshold indicating the highest level of symptoms beyond which a patient considers himself or herself well.

Use of these values enables the investigator to dichotomize outcomes by identifying which patients did and did not exceed the threshold.

Finally, they propose a “clinical relevance ratio,” which reports the number of patients achieving clinical importance at a given time point divided by the total number of patients included in the study at its outset.

Unlike other common PROM-reporting approaches, the clinical relevance ratio is not skewed by patients who are lost to follow-up with increased time after the procedure; it is recognized that the more-satisfied patients are reported to be more likely to follow up, introducing response bias with an increasing loss to follow-up (see this link and this link).

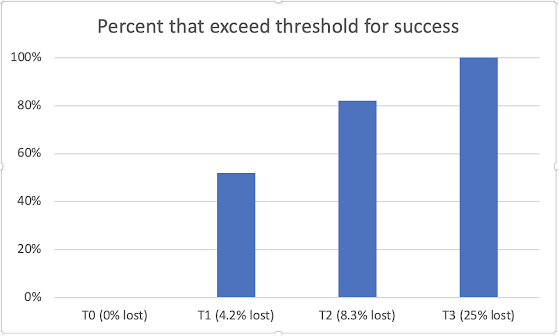

Consider the example below. Preoperatively (T0) all 120 patients scored below the PASS.

At T1, 5 patients had been lost to followup - 52% (60/115) of the remainder exceeded the PASS.

At T2, 10 patients had been lost to followup - 82% (90/110) of the remainder exceeded the PASS.

At T3, 30 patients had been lost to followup (including all those failing to exceed the PASS at T2) - 100% (90/90) of the remainder exceeded the PASS. This could be reported as a 100% success rate at final followup.

Comment: Previous posts (see this link for example) have discussed non-response bias. This is why it is important to use followup methods that minimize the risk of non-response (i.e. loss to followup). The prevailing wisdom is that loss to followup is minimized when mail-in forms are used and when the non-responders are pursued by followup mailings and phone calls. This obviates the biasing effects of requiring patients to return to the office or of requiring patients to use a computer interface.

Follow on twitter: https://twitter.com/shoulderarth

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frederick.matsen

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

How you can support research in shoulder surgery Click on this link.

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interest