Dwight D. Eisenhower, our 34th President, said “the plan is nothing, planning is everything”, meaning that while specific plans may change, the act of planning itself is crucial because it prepares us to anticipate, adapt and respond effectively.

Thus, while there are important qualities of each patient’s arthritic shoulder that are only be revealed once the osteophytes have been removed and the contracted soft tissues are released, we can anticipate some elements of the surgery with consideration of the patient’s pre surgical anatomy as seen on plain radiographs and the preoperative physical examination.

Michael Hachadorian, one of our current fellows, put together this blog post addressing this topic. He pointed to 4 major considerations that can help guide us in the planning of the shoulder arthroplasty

(1) Is the patient a better candidate for an anatomic total shoulder or for a ream and run procedure?

(2) Is the patient stiff (i.e. <100º of presurgical forward elevation and ≤0º of external rotation)?

(3) Does the patient exhibit posterior decentering on the preoperative axillary “truth” view?

(4) Is "overstuffing" only a humeral problem, or is it a potential issue with the global lateralization that can accompany the addition of a polyethylene glenoid component? (see Seven ways to overstuff an anatomic arthroplasty)

Here he presents five cases as illustrations of an approach to preoperative planning for shoulder arthroplasty that does not utilize CT scans or 3D planning software.

Case 1, The preoperatively centered, stiff arthritic shoulder

Here is a 44 year old male with severe OA who desired a ream and run. His preoperative examination revea

His plain radiographs showed many loose bodies and osteophytes. His axillary “truth” view shows a humeral head centered on an A2 type glenoid, suggesting that posterior instability is unlikely to be an issue with this shoulder.

In this case the most important thing is to restore mobility to this shoulder, rather than trying to restore the "premorbid" anatomy.

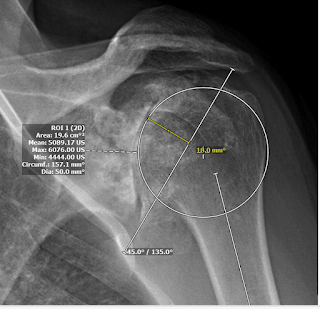

The PACS (Picture Archiving and Communication System) is available to most shoulder surgeon. It has tools for “trying” different prosthetic head sizes as shown below.

50 mm diameter of curvature.

54 mm diameter of curvature

The 54 diameter of curvature intersects the 3 points of the “perfect circle” and reveals the medialization resulting from arthritic humeral head bone loss. However, given the considerable presurgical stiffness that is likely to recur after surgery despite vigorous soft tissue relases, one can anticipate that the 50 mm diameter of curvature might be a better choice if confirmed by intraoperative testing.

Using angle tool at 135º relative to the humeral shaft, the PACS tools can then be used to explore the location of the head cut for this size head component, including its relation to the cuff insertion superiorly and to the osteophytes inferiorly.

Based on this head cut, the thickness of the humeral head implant can be estimated measuring the distance from the medial aspect of the circle to the cut line. This example shows a 20 mm thickness head component.

Intraoperatively, both of these configurations were trialed and it was found that the range of motion was better with the 50 18 head and the stability was adequate. Here is the postoperative film with the 50 18 in place.

With the subscapularis closed his forward flexion was 165 degrees and his external rotation 30 degrees.

Case 2, The preoperatively decentered, stiff arthritic shoulder

This patient is an active 64 M who desired a ream and run procedure. His preoperative exam showed 90º forward elevation, external rotation at the side of 10º, external rotation in abduction to 30º, internal rotation in abduction to 0, and cross body adduction of 30 cm to contralateral acromioclavicular joint.

His preoperative x-rays are shown below. His axillary “truth” view demonstrates essentially complete posterior decentering on a posteriorly eroded glenoid.

So here we have the challenging combination of stiffness and posterior instability. How can preoperative planning guide our efforts?

A 54 size head seems to fit well, but there was concern about posterior instability with an "anatomic" humeral reconstruction given his preoperative decentering. Note that while in the previous example, we elected to “undersize” the humeral head, we anticipate that the same strategy in this case could increase concern about postoperative instability.

On the “truth” view about 75% of the humeral head would lie posterior to the perpendicular bisector of the glenoid face.

We marked out the head height (18 mm) and the desired cut angle 135º. This head position would leave a 1 mm berm. We wanted to avoid a "too high" head because a head that is high with the arm at the side is posterior with the arm flexed forward at 90º

However, at surgery after osteophyte resection and anterior soft tissue releases, the planned 54 18 concentric head component was (as anticipated) posteriorly unstable.

As a result, a 54 18 anteriorly eccentric humeral head was placed on a short stem (selected to assure implant stability in the humerus).

The postoperative AP view shows the head in the planned position.

The reconstruction did not substantially alter the global lateralization in comparison to the preoperative position.

The postoperative “truth” view shows the anteriorly eccentric humeral head centered on the glenoid that was reamed conservatively without glenoid version "correction".

This reconstruction provided a stable shoulder with postoperative flexion to

Case 3 Total shoulder with overstuffing resulting from the addition of the glenoid polyethylene.

While focus on the reconstruction of the humeral head is reasonable for ream and run surgery, the effect of the addition of a 4 mm thick polyethylene glenoid component in total shoulder arthroplasty needs to be accounted for. In these cases, an anatomically reconstructed humeral head may lead to excessive global lateralization and resulting stiffness.

Here are the preoperative radiographs from a patient who had longstanding shoulder OA and was notably stiff on preoperative examination (FE 80, ER to 10, ERA 20 and IRA 10).

In this case, 50 x 20 appeared to be like a reasonable option to re-create humeral anatomy.

Post-operative radiographs demonstrated re-creation of humeral anatomy.

Case 4. Total shoulder with undersizing of the humeral head to accommodate the stuffing effect of the glenoid component.

Here are preoperative radiographs from a patient who had longstanding shoulder OA and was notably stiff on preoperative examination (FE 90, ER to neutral, ERA 10 and IRA 10). The “truth” view did not indicate posterior instability.

A head size of 54 would nicely reapproximate the patient’s humeral anatomy,

Downsizing to a size 50 x 18 head would avoid excessive global lateralization once the thickness of the glenoid component is factored in.

The revised plan is shown below

And here is the postoperative x-ray

While the humeral component may appear to be undersized, the reconstruction did not increase the global lateralizing, avoiding tightening of the shoulder.

The humeral head remained concentric on the postoperative “truth” view despite under sizing the humeral head component.

Case 5: Total shoulder in a posteriorly decentered humeral head without stiffness.

An anatomic head cut was templated using a 50 20 humeral head.

During surgery, it was determined that an anterior eccentric humeral head was needed given persistent posterior instability with all head sizes. After trialing the 50 20 anterior eccentric head offered the desired stability.

Comment: First of all, thanks to Mike for the heavy lifting in putting this together. Second, thanks to all our past shoulder fellows and colleagues such as Armodios (Armand) Hatzidakis and Surena Namdari for their active role in continuing to shape our thoughts about shoulder arthroplasty.

You can support cutting edge shoulder research that is leading to better care for patients with shoulder problems, click on this link

Follow on twitter/X: https://x.com/RickMatsen

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/shoulder.arthritis

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interest

Shoulder arthritis - what you need to know (see this link).

How to x-ray the shoulder (see this link).

The ream and run procedure (see this link).

The total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The cuff tear arthropathy arthroplasty (see this link).

The reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The smooth and move procedure for irreparable rotator cuff tears (see this link)

Shoulder rehabilitation exercises (see this link).