A few words at the start:

(1) Here I show a basic approach to stretching for the shoulder that has limited range of motion (i.e. stiffness of the glenohumeral joint). Note that in this post we'll be using the classic illustrations drawn by Steven B. Lippitt.

(2) Often the stiff shoulder has limited motion in multiple directions (shown below for a stiff right shoulder)

Forward Flexion

(3) Before starting the exercises, the patient should check with the treating physician to make sure they are safe and appropriate. This is especially the case after surgical procedures when tendons, muscles or bone have been repaired.

(4) Stretching is most likely to be successful if the joint surfaces of the shoulder are smooth - rather than when there is significant arthritis. However, these exercises may be helpful with mild-moderate arthritis.

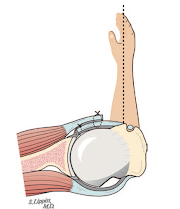

(5) Stretching exercises are designed to restore flexibility of the fibrous tissue that surrounds the joint - the capsule - the dark tissue shown surrounding the socket on this view of the inside of the shoulder

(6) These exercises can be effectively carried out by the patient without a therapist (once the physician has given the OK). The exercises shown here require minimal equipment and can be done just about anywhere. Relaxation and patience are essential, however.

(7) For each exercise shown, the stiff arm is helped with the arm on the opposite side so that the muscles around the stiff shoulder can completely relax. The arm is moved to the point where tightness is felt and held there for a minute by the clock during which time a gentle stretch is applied while the muscles remain relaxed. Three sets of the stretches are performed three times a day, striving to make a small, but noticeable gain in the range of motion each time.

(7) Any discomfort from the stretching exercises should subside within 20 minutes. If pain lingers longer than than, the exercises should be performed with less vigor, but still continued regularly.

(8) Here are the basic stretches. I've included links to videos I put together a while back.

A. Assisted Forward Flexion

Video: Forward Elevation: Supine

Follow on twitter/X: https://x.com/RickMatsen

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/shoulder.arthritis

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interest

Shoulder arthritis - what you need to know (see this link).

How to x-ray the shoulder (see this link).

The ream and run procedure (see this link).

The total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The cuff tear arthropathy arthroplasty (see this link).

The reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The smooth and move procedure for irreparable rotator cuff tears (see this link)

Shoulder rehabilitation exercises (see this link).