Complications of reverse total shoulder while the surgeon learns the procedure

Clinical outcomes and complications of cementless reverse total shoulder arthroplasty during the early learning curve period

These authors investigated the early functional outcomes and complications of cementless reverse total shoulder ( RTSA ) during a surgeon's early experience (the learning curve period).

These authors investigated the early functional outcomes and complications of cementless reverse total shoulder ( RTSA ) during a surgeon's early experience (the learning curve period).

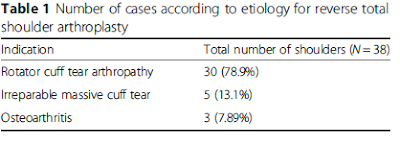

They retrospectively evaluated 38 shoulders having this procedure (6 male, 32 female), average age 73.0 years (range, 63 to 83 years) with average followup of 24 months (range, 12–53 months).

The VAS score improved from 4.0 to 2.8 (p = 0.013). The UCLA score improved from 16.0 to 27.9 (p = 0.002), and the Constant score improved from 41.4 to 78.9 (p < 0.001).

Postoperative complications occurred in 16%, including acromion fracture (one case), glenoid fracture (one case), peripristhetic humeral fracture (one case), axillary nerve injury (one case), infection (one case), and arterial injury (one case).

Comment: The results of this small study should be compared to those of a larger recent study

This is a very important article. It details the odyssey of an experienced shoulder surgeon to learn to do the reverse total shoulder. The concept of a learning curve is critical to every surgical procedure - how can individual surgeons achieve mastery? It is important to recognize that the learning curve is not only about surgical technique, but also about patient selection, in-hospital management, and rehabilitation.

As shown in the figure below from this article, experience is a great teacher. The rate of local complications was over 20% for the first 40 shoulders and less than 7% for the last 160 shoulders.

The most common complications were transient neuropathy, intraoperative fracture, postoperative dislocation, incompletely seated glenosphere, intraoperatively broken screw head, broken drill bit, chronic subluxation, acromion fatigue fracture, and painful cerclage wires. Perioperative systemic complications occurred in 5% of the cases.

This study brings to the fore the topic of surgeon experience and case volume. It has been shown that the quality of outcome is related to surgeon case volume. The explanation may like in the fact that low volume surgeons remain at the left hand side of the learning curve shown above.

==

These studies ask, but do not answer two important questions: (1) "what is the complication rate after reverse total shoulder" and (2) "how many cases does it take before a surgeon masters this procedure?"

Answering these questions is complex. First of all "the surgeon is the method", i.e. different surgeons have different levels of experience with shoulder arthroplasty and different rates of skill acquisition: some will master this procedure much more quickly than others. Second, the published literature presents predominantly data from high volume centers, so that the learning curve effect and the complication rates are unlikely to be representative of the community surgeon performing a small number of shoulder arthroplasties per year.

This fact is exemplified by comparing the complications reported in the literature in comparison to those reported to the FDA:

Analysis of 4063 complications of shoulder arthroplasty reported to the US Food and Drug Administration from 2012 to 2016

These authors point out that most of the literature on shoulder arthroplasty failure comes from high-volume centers and that these reports tend to exclude the experience of community orthopedic surgeons, who perform most of the shoulder joint replacements.

They analyzed the failure reports mandated by the US Food and Drug Administration for all hospitals. Each reported event from 2012 to 2016 was characterized by implant, failure mode, and year of surgery.

For the 2390 reverse arthroplasties, the most common failure modes were dislocation/instability (32%), infection (13.8%), glenosphere-baseplate dissociation (12.2%), failed/loosened baseplate (10.4%), humeral component dissociation/tray fracture (5.5%), difficulty inserting the baseplate (4.8%), and difficulty inserting the glenosphere (4.2%).

The percentage distribution of the failure modes also differed substantially from those published in a recent review of the literature.

The publicly available Food and Drug Administration database reveals modes of shoulder arthroplasty failure that are not emphasized in the published literature, such as rotator cuff tear, infection, and postoperative pain/stiffness for anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty and implant dissociation and baseplate failure for reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

The freely accessible FDA MAUDE database is a resource for identifying failure modes for shoulder arthroplasty not readily identified in the published literature. Some modes of failure appear in the MAUDE data base long before they appear in the published literature, such as the dissociation of the glenosphere from the the baseplate as shown below.

===

We have a new set of shoulder youtubes about the shoulder, check them out at this link.

Be sure to visit "Ream and Run - the state of the art" regarding this radically conservative approach to shoulder arthritis at this link and this link

Use the "Search" box to the right to find other topics of interest to you.

You may be interested in some of our most visited web pages arthritis, total shoulder, ream and run, reverse total shoulder, CTA arthroplasty, and rotator cuff surgery as well as the 'ream and run essentials'