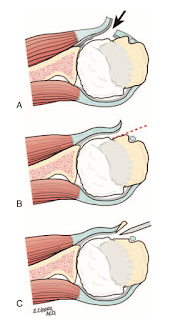

The surgical exposure of the joint for anatomic shoulder arthroplasty almost always requires subscapularis tenotomy (A) or detachment of the subscapularis tendon from the humerus using a peel (B) or a lesser tuberosity osteotomy (C).

At the conclusion of the procedure the tendon is repaired securely

The subscapularis reattachment can be reinforced by a plication of the rotator interval (arrow).

and Histologic characteristics of the subscapularis tendon from muscle to bone: reference to subscapularis lesions

For the reasons stated above, it is not surprising that many patients fail to regain normal subscapularis function after shoulder arthoplasty (see The return of subscapularis strength aftershoulder arthroplasty).

For the first few months after surgery, the application of passive and active loads to the subscapularis repair can cause its failure. Thus it is recommended that the exercises shown below are avoided for this period.

Even with the commonly prescribed external rotation stretch, the hand force moment is many times the subscapularis load moment, magnifying the load on the subscapularis tendon

A recent article, Functional and Radiographic Results of Anatomic Total Shoulder Arthroplasty in the Setting of Subscapularis Dysfunction: 5-year Outcomes Analysis identified 668 patients having two year followup after anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty; the subscapularis was managed with either a peel or a lesser tuberosity osteotomy. Postoperatively, the patients were placed in a sling for six weeks with pendulum exercises three times per day.

For the first few months after surgery, the application of passive and active loads to the subscapularis repair can cause its failure. Thus it is recommended that the exercises shown below are avoided for this period.

Even after the first few months, certain exercises put the subscapularis at - perhaps unexpected - risk.

To help see why, consider our high school physics lesson in equilibrium:

force 1 times moment arm 1 = force 2 times moment arm 2

In the "fly" shown below, the subscapularis is subjected to substantially greater loads than the force applied by the hand.

This is because the moment arm for the hand force is many times the moment arm of the subscapularis load opposing it.

Muscular individuals may be especially at risk for early post operative subscapularis failure because seemingly minor events or accidents may produce enough force to damage the repair.

34 of these patients (5%) demonstrated subscapularis dysfunction as manifested by the inability to hold the hand on the belly while the elbow was placed anterior to the plane of the body.

Notably this physical examination test was used rather than ultrasound, MRI or contrast CT, each of which can be difficult to interpret after shoulder arthroplasty because of the metal artifact.

In comparison to those without subscapularis dysfunction, patients with subscapularis dysfunction demonstrated worse postoperative Simple Shoulder Test, SANE, VAS Function, VAS Pain, and ASES scores, as well as lower rates of satisfaction and worse active range of motion. Only 47% of the patients could reach the small of their back compared to 85% with normal subscapularis function.

Patients with subscapularis dysfunction had higher rates of anterior subluxation (see example below)

as well as higher rates of revision.

In spite of the poorer outcomes in patients with subscapularis dysfunction, most of these patients were improved in comparison to their preoperative status.

Notably, when subscapularis failure was suspected during the early postoperative period, the authors did not immediately recommend revision surgery, rather waiting to see if function and comfort will improve.

Comment: It can be concluded that (a) a robust subscapularis repair and (b) protection of the repair during healing are of great importance to assure the optimal outcome from anatomic arthroplasty.

Re-repair is a consideration if there is evidence of tendon failure, especially if there has been a sudden event soon after arthroplasty. The authors of Clinically significant subscapularis failure after anatomic shoulder arthroplasty: is it worth repairing? compared minimum 1 year results with subscapularis failure after anatomic arthroplasty having subscapularis re-repairs to those having conversion to reverse total shoulder. Patients having re-repair were significantly younger than patients who underwent revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (mean age, 59.3 years vs. 70.3 years, had a better comorbidity profile, and had a more acute presentation (mean time between injury and surgery, 9.1 weeks vs. 28.5 weeks.

Re-repair is a consideration if there is evidence of tendon failure, especially if there has been a sudden event soon after arthroplasty. The authors of Clinically significant subscapularis failure after anatomic shoulder arthroplasty: is it worth repairing? compared minimum 1 year results with subscapularis failure after anatomic arthroplasty having subscapularis re-repairs to those having conversion to reverse total shoulder. Patients having re-repair were significantly younger than patients who underwent revision to reverse shoulder arthroplasty (mean age, 59.3 years vs. 70.3 years, had a better comorbidity profile, and had a more acute presentation (mean time between injury and surgery, 9.1 weeks vs. 28.5 weeks.

Patients who underwent subscapularis re-repair also had a significantly higher reoperation rate (52.9% vs. 0.0%); this is expected in that older patients are unlikely to want or have a revision of a reverse total shoulder within the first year after the procedure, whereas younger patients having an attempted re-repair may consider another surgery. It is apparent that re-repair of a failed subscapularis is more likely to fail than the original repair performed at shoulder arthroplasty because the diagnosis is often delayed and the quality of the tissue is poorer.

At final follow-up, functional outcomes scores and patient satisfaction rates were not significantly different between treatment groups.

The biggest challenge lies in the management of the young strong patient having subscapularis failure after anatomic total or ream and run arthroplasty. These patients are often in their 30s or 40s and want to avoid conversion to a reverse total shoulder because of their young age and activity expectations.

In these cases, reinforcing the repair with a tendon graft becomes a consideration (see The subscapularis: anatomy, failure and reconstruction and The subscapularis).

Thanks to Mihir Sheth, UW shoulder fellow, for his help in preparing this post.

You can support cutting edge shoulder research that is leading to better care for patients with shoulder problems, click on this link.

Follow on twitter (X): https://twitter.com/shoulderarth

Follow on facebook: click on this link

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frederick.matsen

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interest

Shoulder arthritis - what you need to know (see this link).

How to x-ray the shoulder (see this link).

The ream and run procedure (see this link).

The total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The cuff tear arthropathy arthroplasty (see this link).

The reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The smooth and move procedure for irreparable rotator cuff tears (see this link).

Shoulder rehabilitation exercises (see this link).

The biggest challenge lies in the management of the young strong patient having subscapularis failure after anatomic total or ream and run arthroplasty. These patients are often in their 30s or 40s and want to avoid conversion to a reverse total shoulder because of their young age and activity expectations.

In these cases, reinforcing the repair with a tendon graft becomes a consideration (see The subscapularis: anatomy, failure and reconstruction and The subscapularis).

Thanks to Mihir Sheth, UW shoulder fellow, for his help in preparing this post.

You can support cutting edge shoulder research that is leading to better care for patients with shoulder problems, click on this link.

Follow on twitter (X): https://twitter.com/shoulderarth

Follow on facebook: click on this link

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frederick.matsen

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interest

Shoulder arthritis - what you need to know (see this link).

How to x-ray the shoulder (see this link).

The ream and run procedure (see this link).

The total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The cuff tear arthropathy arthroplasty (see this link).

The reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).

The smooth and move procedure for irreparable rotator cuff tears (see this link).

Shoulder rehabilitation exercises (see this link).