These authors sought to determine whether patients who undergo RTSA are susceptible to recall bias and, if so, which factors are associated with poor recollection.

72 patients completed the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES scores) Standardized Assessment Form at the time of preoperative assessment. Patients were contacted at a minimum of 24 months after surgery to retrospectively assess their preoperative condition.

Patient assessment of their preoperative shoulder condition showed poor reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.453, confidence interval, 0.237-0.623).

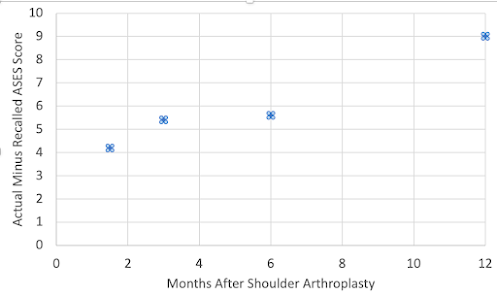

Greater preoperative shoulder ASES scores were associated with a greater difference between preoperative ASES scores and recall ASES scores.

Comment: Patient satisfaction after surgery is based largely on the perceived improvement after the procedure. This study indicates that the perceived improvement may be greater than the actual improvement, especially for patients with less actual pain prior to surgery.

This finding also confounds to a degree the "anchor method" for determining the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for a procedure (see this link). The anchor method asks each patient to rate his or her shoulder as “worse,” “unchanged,” “better,” or “much better” relative to the recalled preoperative condition. The MCID is the minimal difference in the preoperative-to-postoperative outcome measure between patients describing the treatment outcome as “worse” or “unchanged” compared to those describing the treatment outcome as “better.” This study suggests that in this calculation, more patients may be placed in the "better" group than would be justified by their actual postop vs preop scores.

In conclusion, we need to recognize the existence and effects of recall bias in which patients may perceive more improvement than what actually occurred.

You can support cutting edge shoulder research that is leading to better care for patients with shoulder problems, click on this link.

Follow on twitter: https://twitter.com/shoulderarth

Follow on facebook: click on this link

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frederick.matsen

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/

Here are some videos that are of shoulder interestShoulder arthritis - what you need to know (see this link).How to x-ray the shoulder (see this link).The ream and run procedure (see this link).The total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).The cuff tear arthropathy arthroplasty (see this link).The reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (see this link).The smooth and move procedure for irreparable rotator cuff tears (see this link).Shoulder rehabilitation exercises (see this link).

Follow on twitter: https://twitter.com/shoulderarth

Follow on facebook: click on this link

Follow on facebook: https://www.facebook.com/frederick.matsen

Follow on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rick-matsen-88b1a8133/